These coins constitute an overwhelming majority of the activity in the coin market. Interest in collecting regular issue coins probably began in the 1820s or 1830s, when a few curious folks in the Philadelphia and New York area began to notice that a few early coins from the 1790s were getting hard to find. However, it was not until the late 1850s that interest became widespread, and dealers, numismatic publications and auctions began to appear on the scene.

Regular issue coins are collected in two major ways:

1. By series – One attempts to acquire all the different dates, mintmarks and sometimes varieties of a given series. This was popular for many years, and for some series, it is still the leading way to collect. However, some series of the 18th and 19th centuries have gotten out of reach pricewise, for the average collector. If one is collecting by series, there are several approaches, depending largely on one’s interest and pocketbook.

a. The easiest and most affordable way to collect a series is simply by date. That is, one example of each date, regardless of mintmark. This enables one to avoid most of the “key dates” and acquire a complete set at a reasonable price. Using Morgan Dollars as an example, a date set would be just that – one of each year from 1878 through 1904, and the 1921. While a few dates such as 1893 or 1895 would cost a bit more, none are really out of reach for most.

b. Probably the most popular way to collect a series is by date and mintmark. For most 20th century series, this is a realistic goal and while there are some tough dates, most can be acquired without too significant an outlay.

Again, using our Morgan Dollar example, adding all the mintmarks brings in some tougher dates such as the 1889-CC, 1893-S and of course the proof-only 1895-P. While mint state examples of these key dates are quite costly, circulated examples can be acquired more reasonably.

c. The next rung up the ladder is to add major varieties. While it is sometimes hard to determine what is a major variety and what is a minor variety, a good arbiter is the Guidebook of United States Coins (more familiarly known as the “Redbook”). These major varieties typically include overdates, doubled dies, over-mintmarks, and on early series, noticeable differences in the lettering, dates, portrait, number of stars, etc.

For Morgans, if one includes the “Redbook Varieties” you now get into the number of tailfeathers on the 1878s, overdates on the 1880-CC and 1887, a doubled-die reverse in 1901, over-mintmarks in 1882 and 1900 and several others listed in the Redbook.

d. Finally, one can go “all-in” and attempt to acquire all known varieties of a given series. This is usually undertaken only by specialists and advanced numismatists, and follows one of the major references written on a particular series. For example, early Large Cents are collected by Sheldon number, after Dr. William Sheldon’s 1949 book “Penny Whimsey”, early half dollars are sought by Overton number, (Al Overton’s 1967 book) and Morgan Dollars are sometime collected by their VAM number, following the book by Leroy Van Allen and George Mallis. While these three are probably the most popular, references exist for numerous other series such as Half Cents (Cohen), Early Quarters (Browning), and Early Dollars (Bolander) and others. While later research and books have been written revising and updating much of this information, the references mentioned are the traditional benchmarks used by specialists in forming a collection.

The final rung for the Morgan Dollar collector involves the VAM varieties, of which there are approximately 2,000. However even these have been hierarchically arranged, and some VAM varieties are more important than others. The “Top 100” list adds some focus to the effort, for without it, one is faced with an overwhelming number of minor varieties, many of which are of little interest or distinction except to a very few.

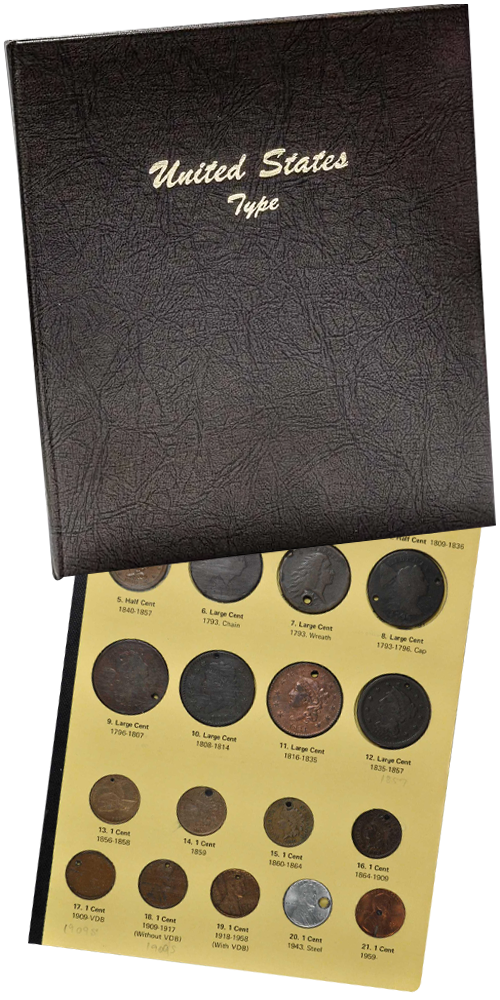

2. By Type – By the 1960s and 1970s, many of the key dates and gotten quite expensive, and many collectors took a new approach to collecting – acquire one example of each distinct type of U.S. coin. So rather than attempting to find or purchase every date and mintmark of an issue, one nice example was sought. This approach also added variety to one’s collection in that no two coins were exactly alike and a far longer time frame could be represented.

The criteria for determining what constitutes a distinct type vs. a variety, is subject to some interpretation. Drawing a line on what should, or should not be included in a type set is not cast in stone, and individual collectors often include or exclude certain varieties depending on their interest and budget. Traditionally, distinct types and varieties have been defined using three criteria.

a. A noticeable change to the device on the obverse or reverse.

b. An addition, deletion or change in the lettering.

c. A change in the metallic alloy from which the coin is struck or the weight of the coin.

While the above sounds fairly straightforward, unfortunately it is not. Changes can range from extremely major, such as the replacement of Gobrecht’s Liberty Seated design by Charles Barber’s design in 1892 on silver dimes, quarters and halves, or extremely minor, such as the addition of Victor D. Brenner’s initials at the base of Lincoln’s bust on the cent in 1918.

Between these two extremes are dozens if not hundreds of modifications that have been made to U.S. coins since their inception in 1792-94 and the decision if a change warrants inclusion in a type set is often a judgement call. For many collectors, that decision is often made by the producers of albums and holders, who provide a “roadmap” by virtue of including (or excluding) a space for a particular type or variety. Let’s take a closer look at each of the three criteria used in determining a type coin.

d. A change to the devices on either the obverse or reverse is the most important criteria considered in defining a type. These however, vary widely in their appearance and impact and range from the complete redesign of the coin to a very subtle “tweaking” of the devices.

It goes without saying that a complete redesign easily qualifies in all type sets by any definition. Reverse changes such as the replacement of the wheat stalks with the Lincoln Memorial on the cent, or more recently, with the shield reverse, are also obvious types. However recent mint issues have complicated that rule somewhat. More on that to come.

Moving to slightly more subtle changes such as replacing the mound with the recessed “flat plain” on the reverse of the 1913 Buffalo nickel, the elimination of the rays on the Shield nickel in 1867, the modifications to the Standing Liberty quarter in 1917 (breastplate on the obverse, three stars under the eagle on the reverse) and the use of arrows on silver coins in 1853 and 1873 are likewise generally recognized as distinct types.

However, other similar changes are generally ignored. To cite a few examples: the $10 Gold Eagles of 1838 and early 1839 have a very distinct obverse, and are almost universally overlooked as a type; the recessed date introduced on the 1925 quarter is seldom mentioned; the earliest Capped Bust halves of 1807-08 feature a noticeably thinner portrait and the addition of drapery to the Seated Liberty coins in 1840 is noted, but seldom seen as a distinct type.

The varying number and arrangement of stars on late 18th century coins is not considered a distinct type nor is the open and closed wreath on 1849 gold dollars, yet the change in the outline of the star on three cent silver coins in 1859 is included in most type albums.

If much of this sounds inconsistent, it is. However much of numismatics is based on tradition and habit, and very often the creators of albums and holders, as well as reference books, have set the parameters for type collectors.

Finally, in recent years, the mint has begun to issue a tremendous variety of reverses, particularly on the quarter, but on the cent and nickel as well. Over 120 different reverses have appeared on the quarter since 1999, and the question arises, do these belong in a type set? The four commemorative reverses on the cent in 2009 and the Westward Journey Nickels of 2004-05 also fall into the same category. All these recent issues have certainly muddied the water and defining a “type set” is more complex now than in the past. Perhaps the answer is one State Quarter, one America the Beautiful Quarter etc… to represent the issue as a whole.

e. Additions, deletions and changes in the lettering appearing on a coin are a second defining characteristic of determining a distinct type. For example, the addition of the word “CENTS” to the bottom reverse of the 1883 Liberty nickel, or the addition of the motto “IN GOD WE TRUST” to the reverse of our larger silver and gold coins following the Civil War are proverbial “no-brainers” and are recognized by all type collectors.

Not all lettering changes are as well-known or universally recognized. Only some type albums or holders note the “No Motto” Eagles and Double Eagles of 1907-08, and the change from TWENTY D. to TWENTY DOLLARS on the reverse of the Double Eagle in 1877 is recognized only by some. The change from “50 CENTS” to “HALF DOL” on the reverse of the half in 1838 is sometimes omitted from some albums, and is combined into the general Reeded Edge type of 1836-1839. It gets even more obscure though.

Designer’s initials are a good example. The “VDB” was removed from the bottom reverse of the Lincoln Cent shortly after its introduction in 1909. What is less widely-known though, was that it was restored in 1918 at the base of Lincoln’s bust. Few if any type collectors take note of this addition. Similarly, the addition of Felix Schlag’s initials to the obverse of the Jefferson Nickel in 1966 passed almost without notice. In short, large lettering changes are likely to be included… small ones, not so much.

f. Changes to the metallic alloy used in striking circulation issues have been going on for well over a century and a half. One of the more recent and widely-known was the elimination of silver from our dimes and quarters in 1965. The introduction of a thin bronze cent in place of the thicker copper-nickel cents in 1864 was also a notable change, and garnered widespread public attention. During the Second World War, the use of silver in our five-cent coin (1942-45), and steel in the one cent coin (1943) were also important substitutions, and these coins are included in virtually all type sets. However, there have been numerous other changes which have largely gone unnoticed.

In 1982, zinc was substituted for bronze in our one cent coin, but because it was plated with pure copper, its appearance did not change and passed largely unnoticed. Speaking of unnoticed; in 1962, the tin was removed from the cent alloy, but even the most advanced type collectors really don’t consider this coin to be worthy of inclusion in a set. Similarly, the cents of 1944-1946 were made from salvaged cartridge cases and contained no tin, but few collectors note this minor alloy change either.

So unless the modification is obvious to the eye, the odds of an alloy change in a coin being included in a type set are slim.

While collecting by series and/or type are certainly the two most popular approaches to building a collection of U.S. regular issues, they are by no means the only paths one can choose. Some collectors with an interest in local or regional history may seek out coins from a particular mint, and attempt to collect all issues from the Charlotte, Dahlonega, Carson City, or New Orleans mint for example. The Liberty Half Eagle (1839-1907) was the only coin struck at all seven mints, and a complete set of those in high grade would be a challenge indeed.

One can focus only on a particular metal, denomination, time period, or designer, and build an interesting collection. Becoming even more creative, one can attempt to collect all coins which bear the same date, but are of a different type. Examples of this include the 1909 cent, which was issued both as an Indian and Lincoln design, the 1938 nickel (both as a Buffalo and Jefferson) and the 1916 dime, both a Barber and Mercury design. There are probably close to twenty such pairings in the regular issue series. Other collectors may also choose to collect modern issues, such as State or National Park Quarters, Presidential Dollars or any of a number of other post-1964 series.

Interesting die varieties such as overdates, doubled dies, over-mintmarks, or blundered lettering are just some of the other areas in which collectors have chosen to specialize. As stated at the start, the scope or focus of your collection is limited only by your imagination and budget!